Admiral Wilson Boulevard, a two-and-a-half-mile section of U.S. Route 30 extending from the Benjamin Franklin Bridge in Camden to the Route 70 overpass in Pennsauken, was the first “auto strip” in the United States. Originally named Bridge Approach Boulevard when it opened in 1926, it was renamed in 1929 to honor Rear Admiral Henry Braid Wilson, a Camden native who served in the Spanish-American and First World Wars. The road had a significant impact on the development of the inner South Jersey suburbs and Camden City in the twentieth century.

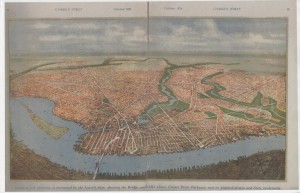

When the Benjamin Franklin Bridge (originally named Delaware River Bridge) opened in 1926, the accompanying egress road on the New Jersey side attracted little fanfare. Yet boosters in Camden envisioned Bridge Approach Boulevard as the flagship road in an automotive-centric civic project known as “Greater Camden’s Gateway to New Jersey.” They hoped the project would elevate Camden’s position in the region and make Camden a “second Brooklyn,” the hub of southern New Jersey.

To this end, the city hired landscape architect Charles Wellford Leavitt (1871-1928) to create an intricate web of highways that would connect Camden to the suburbs all the way to the Atlantic coast. Leavitt was an advocate of the “City Beautiful Movement,” which advanced the idea that the beautification of cities through parks and monuments would have a positive effect on the morals and behavior of their residents. Leavitt believed the entryway into South Jersey should showcase Camden, and city boosters lobbied for a hotel near the foot of the bridge, as well as a civic center. The remainder of the Boulevard, which extended into the suburbs, would feature extensive landscaping and a park with a view of the western tributary of the Cooper River and Camden High School.

It was not long before business interests saw opportunities on the new Boulevard that would alter its original civic goals. When it decided to open its first store in Camden, Sears, Roebuck & Company insisted on a location along the Boulevard, rather than in downtown Camden. The company and the city struck a deal that modified the original plan for a civic center near the western end of the Boulevard, and instead a new Sears with ample parking opened there in 1927. Although the city abandoned the civic center concept, it still influenced the design of the store. Unlike other Sears retail stores it had designed in Boston and Chicago, the architecture firm Nimmons, Carr and Wright adopted the classical revival style for the Camden location, influenced by Leavitt and the City Beautiful Movement.

With the opening of Sears, other businesses envisioned opportunities to appeal to the driving consumer on the Boulevard. In 1933, Camden native Richard Hollingshead Jr. (1900-75) opened the world’s first drive-in movie theater on the north side of Admiral Wilson. Based on a design he worked out in his driveway, Hollingshead combined his blueprints and received a patent on the drive-in theater in 1932. The drive-in resonated with an automobile– and Hollywood-crazed public, and Hollingshead’s first night showing of Wives Beware, in June 1933, was a sellout. In ensuing years, drive-in movie theaters opened all over the country. Unfortunately for Hollingshead, most of the theater owners ignored his patent and he received few royalties from their success. Hollingshead’s own theater struggled to make a profit, as an independent theater owner during the studio era he had to pay upwards of $400 for each film shown, and many of the pictures had already shown at traditional theaters before he acquired them. Hollingshead sold the theater in 1935 to a Union, New Jersey, theater owner who relocated the screen and equipment to that city.

Other automotive entertainments were attempted on the Boulevard, including the “whoopee coaster,” a Depression-era attraction in which drivers could take their cars on a series of roller coaster-like tracks. Unlike Hollingshead’s drive-in, the whoopee coaster failed to gain national footing.

Changing City, Changing Boulevard

Businesses continued to grow and expand through the 1950s and 1960s. Several car dealership franchises found success on Admiral Wilson, jointly declaring it “the right route for savings” in a 1952 newspaper advertisement, and motels thrived on both sides of the Boulevard. The opening of a bar in 1949 called The Admiral prompted Henry Wilson to unsuccessfully petition the city to remove his name from the Boulevard, after which he vowed never to travel on the road again.

In the 1970s a business model that had not been seen before on the Boulevard emerged: the go-go club. A Camden City ordinance passed in 1977 restricted businesses related to “prurient interests” to Admiral Wilson Boulevard and banned such businesses from the rest of the city. By the 1980s, adult-themed clubs, hourly rate motels, and other businesses related to sex work dominated the southeastern end of Admiral Wilson. At the same time, Camden’s uptick in crime left employees and customers of these businesses vulnerable to robberies, assaults, and other crimes. In addition to the clubs and motels, many sex workers lined the Boulevard working outside the sanctioned businesses. As these new businesses thrived, the car dealerships and retail businesses that had been at the heart of the Boulevard for much of its existence closed or moved to new suburban locations, following Sears, which left Camden for Moorestown in the early 1970s.

The Gateway Project

In the 1990s, the state of New Jersey and the Delaware River Port Authority (DRPA) proposed a new plan for the road that would incorporate the original tree-lined design with new development. Called the Gateway Project (later expanded to the Gateway Redevelopment Plan), the proposal called for the destruction of a majority of the businesses on the southeast end of the Boulevard, to be replaced by a park along Cooper River with paths for pedestrians and cyclists.

The plan remained dormant until the national Republican Party announced it would hold its 2000 presidential nominating convention in Philadelphia. Convention planners expected many delegates would stay in hotels in the South Jersey suburbs, using the Ben Franklin Bridge and Admiral Wilson Boulevard to commute back and forth to the city. With that prospect in mind, New Jersey’s Republican governor, Christie Todd Whitman (b. 1946), seized the opportunity to accelerate the Gateway Project by pledging $45 million to “restore Admiral Wilson Boulevard to the beauty that it enjoyed long ago.” Thus beginning in 1999, demolition of the strip clubs, hourly motels, and other businesses advanced, and by the time the Republican National Convention opened in late July 2000 the south side of Admiral Wilson Boulevard once again resembled the tree-lined road imagined in the original design, with a public park to be completed at a later date. There were exceptions: A new gas station and mini-mart opened on the south side of the road along Cooper River, and the Sears Building remained on the Boulevard until it too was demolished in 2013.

At the other end of the Boulevard, the planned Gateway Park project had yet to be implemented as of 2015. Runoff gas and oil as well as remnants of the demolished buildings required an environmental cleanup in order for the space to be suitable for public use.

Throughout the twentieth century, Admiral Wilson Boulevard played a significant role in expanding Camden’s retail center from downtown and facilitating the exodus of that center to the suburbs. Originally designed to be a “gateway to Camden,” the Boulevard became a gateway through the city to both the inner and developing outer suburbs. In the twenty-first century, the Boulevard reflects the tree-lined road imagined by Leavitt as well as a new focus on corporate office parks influenced by twentieth century suburbia. One consistency was Admiral Wilson Boulevard’s debt to the driving public. With over one thousand parking spaces, the new office park on the old Sears site would continue the auto-centric nature of the Boulevard.

Bart Everts is a reference librarian at the Paul Robeson Library at Rutgers University-Camden and teaches history at Peirce College. (Author information current at time of publication.)